Background-The State of the Textbook Market

In 2016, the publishing industry was finally forced to acknowledge that the poor performance of higher education textbook publishing was being negatively affected by trends that are structural, rather than cyclical, in nature.

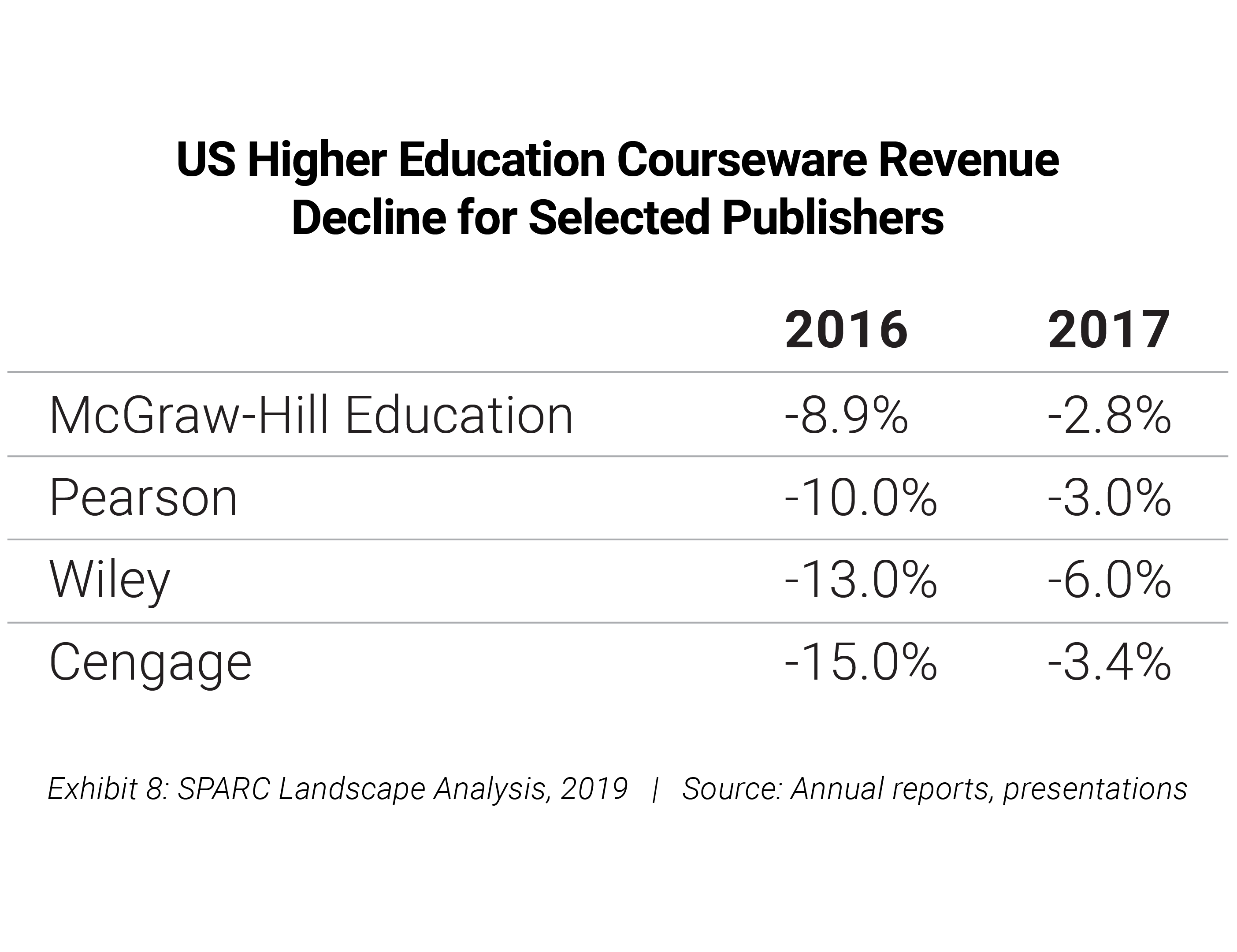

McGraw-Hill Education reported a -8.9% decline for domestic higher education revenues in the FY ending on the 31st December 2016.The events of 2016 were startling: at the end of 2015, Pearson’s management expected U.S. higher education revenues to decline by 1 or 2%, reflecting a similar decline in college enrollment and flat spending per student – while holding market shares stable. By the end of 2016, results were much worse: organic revenue decline in courseware was -10%. Wiley reported even worse results: for the fiscal year (FY) ending in April 2016, textbooks sales declined by -15%, and for the FY ending on the 30th April 2017 organic revenues declined by a further -13%. McGraw-Hill Education reported a -8.9% decline for domestic higher education revenues in the FY ending on the 31st December 2016. Finally, Cengage reported for the fiscal year ending on the 31st March 2017 a revenue decline of -15% for the domestic Learning business.

The publishers entered 2017 with significant misgivings. Even if Pearson blamed a one-time inventory adjustment amongst bookstores for the revenue decline of 2016, its guidance for the following year implied a further 6-7% decline in underlying demand for textbooks and courseware in 2017 (management indicated that revenues may come in between +1 and -7%, depending on stocking strategies of retailers). Against such dire scenarios, the -3% organic revenue decline of 2017 was almost a relief, and it led management to issue a slightly improved guidance for a further -6% decline in demand for courseware in 2018 (against a previously issued guidance of -6 to -7%). Once again, other publishers posted similar or even worse numbers: Wiley reported a -6% revenue decline for textbooks in the FY which ended on the 30th April 2018, McGraw-Hill Education Higher Education revenues declined by -2.8% and Cengage a -3.4% decline in domestic learning revenues for the FY ending on the 31st March 2018 (Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8

US Higher Education courseware revenue decline for selected publishers.

The continued decline of the higher education courseware business in the U.S. is driven by the interplay of three factors: student enrollment, pricing, and participation rates.

Factor 1: Student Enrollment

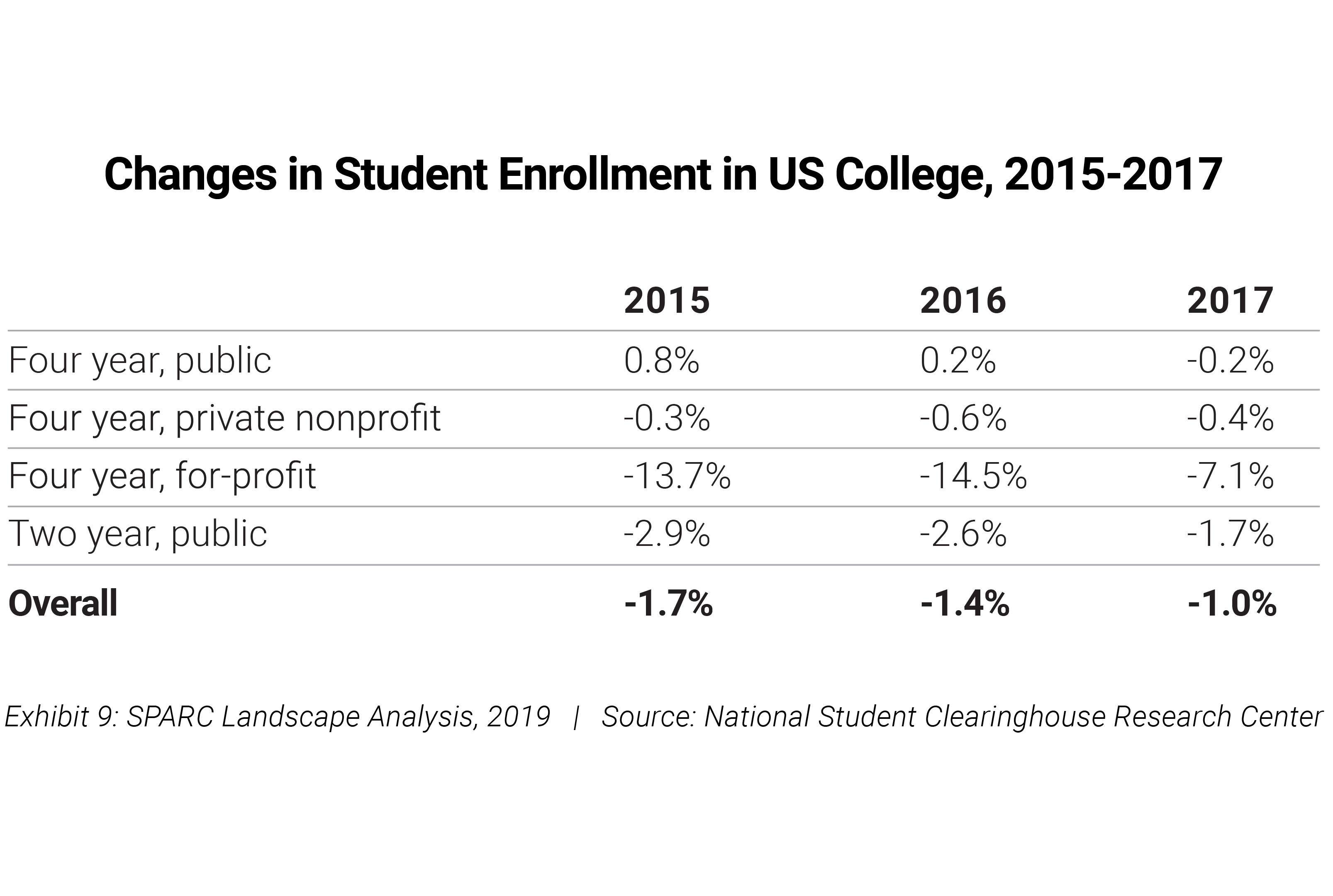

The first factor of student enrollment is cyclical in nature based on the economy (even if there are longer term trends in terms of participation). Pearson estimates that every 1% change (up or down) in the U.S. unemployment rate drives a 3% change (in the opposite direction) in the U.S. college enrollment rate. The robust labor market of 2016 and 2017, therefore, could be expected to drive down enrollment rates in college, which – in fact – declined by -1.4% in 2016 and by -1.0% in 2017 (Exhibit 9). Drops were not equal across all categories of institutions; however, for-profit and community colleges continue to show above average rates of decline, while both public and private non-profit four-year colleges show below average rates of decline (or some modest growth).

Exhibit 9

Changes in student enrollment in US colleges, 2015-2017

Factor 2: Pricing

Assessing changes in average pricing is rather difficult. Contrary to trade books, college textbooks do not have uniform suggested retail prices. College and digital bookstores therefore are free to set any mark-up above the wholesale price set by the publisher. In addition, in the transition from print to digital, publishers can lower their wholesale prices to reflect lower costs, such as the savings on printing, binding, shipping, and warehousing costs (which account for an estimated 7% of publisher revenues and 9% of costs). In fact, because of the potential to sell digital materials directly to students, publishers could stand to increase their revenues despite lower prices by appropriating at least part of the estimated average 25% mark-up practiced by bookstores. Also, “inclusive access” (a model where a time-limited subscription to digital textbooks is automatically charged to students) allows publishers to also increase overall revenues by increasing their sell-through rate and potentially convincing institutions to subscribe to a broader range of content.

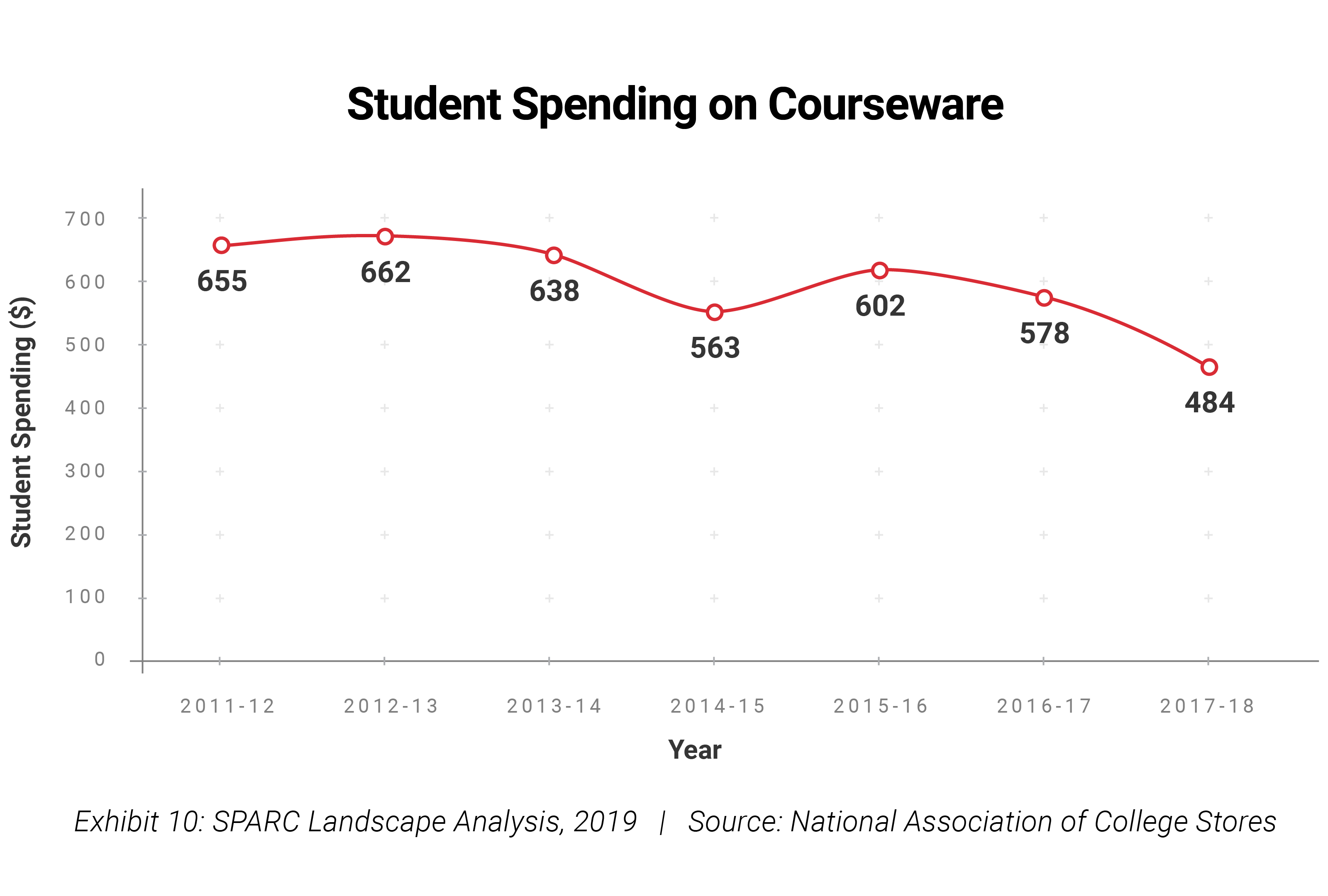

Student spending habits may show some impact on price changes. The annual student survey published by the National Association of College Stores suggests that student spending on textbooks has declined over recent years, thanks at least in part to a variety of strategies to access the materials, including textbook rentals, alternate editions, and used books (Exhibit 10). However, other studies suggest that students opting out of purchasing textbooks likely also contributes to the decline in student spending, which calls into question whether students are in fact better off.

Exhibit 10

Student spending on courseware continues to decline according to some sources.

Product mix also influences realized prices. Follett explains a fairly broad range of options and prices: for a $100 print textbook being sold new in a college bookstore, the used version will command about $75, rental should cost anywhere between $50 and $65, digital editions will retail anywhere between $40 and $60 and custom editions (which are assembled exclusively for a specific campus) will retail at $30. Custom programs are arrangements in which the publishers produce materials that are specifically customized for a course by assembling chapters and articles from multiple sources. These materials are often offered at a steep discount, in large part because of the increased sell-through rate, since students are unable to seek used or rental copies off campus. This has a similar effect as inclusive access, and though different, sometimes the two approaches are combined. As the availability of lower cost options have proliferated over the last decade, it is easy to see how average spending could appear to be in decline.

Factor 3: Participation Rates

Student participation rates (the rate at which students buy new books) are also difficult to assess. The National Association of College Stores survey indicates that 63% of college students buy new books, 56% buy used books and 25% acquire digital materials. This data does not paint the full picture, since most students apply a mixed strategy based on the available options and whether they believe they may need the textbook beyond completion of the class. Most publishers mention seeing market research pointing to about 25 to 33% of students in an average U.S. college course buying new books, about 50% buying used books and the balance resorting to other strategies (borrowing, renting, photocopying, just not using any course material, etc.)

This factor is perhaps the most controversial driver of structural change in the market. Until a couple of years ago, publishers maintained that student segments are different, and that students who buy new books are unlikely to shift to renting, borrowing, or even buying used books. Since the sharp decline in 2016, however, publishers started to review their beliefs. Pearson’s management, for example, has been conceding for about two years that renting is indeed affecting demand for new books.

In general, there is a sense that publishers have limited knowledge of the drivers of student behavior, and that much of what determines how a student will behave is still unknown. In part, this limited knowledge is the legacy of a cultural bias among the publishers, who have always viewed college professors as their true customer, as they are the ultimate decision makers responsible for adopting textbooks. This attitude will change; for example, Pearson’s Chief Strategy Officer comes from Kantar, WPP’s market research unit and is likely to make a major effort to change the culture of the company and spend more resources to understand students and their needs and choices (in order to more effectively market to them).

The Rise of “Inclusive Access”

In 2017, for the first time Pearson’s North American digital higher education revenues were higher than print revenues. For McGraw-Hill Education, digital learning solutions accounted for 62% of revenues in 2017. At Cengage, in the FY ended on the 31st March 2018, digital solutions accounted for 53% of learning revenues. While these numbers still leave most students in most courses using print materials once the used and physical rental markets are taken into consideration, it still means that the rising adoption of digital solutions in the years to come will generate vast amounts of data on students and the teaching performance of faculty.

Publishers are responding to these negative trends by actively supporting “inclusive access.” In its simplest form, inclusive access is an arrangement where a digital subscription to required course materials is included when students enroll in a course by a price pre-negotiated with the publisher. The institution may recover the cost of these subscriptions by directly billing student accounts for each applicable course or by building the cost of course materials into tuition and fees (the latter is less common right now, but is likely to grow with ongoing state and federal lobbying efforts by the publishing industry). While an opt-out mechanism is typically made available for students who wish to purchase their course materials on their own (it is required by U.S. federal regulations under 34 C.F.R. Sec. 668.164(c)), processes are far from streamlined and students may miss the narrow window of opportunity to opt- out. Some inclusive access programs include a flat-rate subscription to a publisher’s catalog of digital materials. Theoretically, students could lower their cost of acquiring books across courses by effectively replacing individual purchases with an annual subscription. However, much remains to be seen.

Consortia like Unizin are beginning to act as aggregators around the inclusive access model, negotiating lower rates across publishers so that students do not have to pay for individual subscriptions (akin to how Spotify or Apple Music aggregate content across major music companies and make it available to consumers through a single subscription, instead of forcing consumers to subscribe to the catalog of each recorded music company). From the publishers’ perspective, the combination of lowering costs (because digital materials replace print books), adding users (because very few students opt out and because there are no books feeding the used book market), and the potential to reduce distribution costs by circumventing bookstores means that the economics of these aggregated subscriptions can be equal or better.

On its face, some argue that inclusive access is a win-win situation for both publishers and students: equal or higher profits for publishers and lower, more predictable spending for students. However, things are not as simple as they appear, particularly for students. All the students who lower their spending by reselling books, renting them, sharing them, or by checking them out of libraries may not be better off (and the lowest spenders will be worse off), depending on actual prices for new and used books and the cost of inclusive access deals. There is also no mechanism preventing publishers from resuming their historical rate of price increases once the model becomes widespread. Most important for the purposes of the issues raised in this document, once students transition to digital materials it enables both their institutions and the commercial vendors to collect vast amounts of data on them: their physical location when they use them, their study habits, their learning profile, and granular knowledge on their performance. This poses significant privacy issues, and – potentially – legal liabilities which could become, at some point, very grave.

Inclusive access is beginning to draw legal challenges. In January 2019, a used bookseller filed a complaint against Trident Technical College (TTC) in South Carolina. The suit alleges that TTC made it hard for students to determine the price of inclusive access materials and for making opt out procedures difficult or unfeasible. The court documents also state that the inclusive access contract with Pearson required TTC to meet a quota in order to be guaranteed a discount, which illustrates the kind of Faustian bargain these deals can entail. The contract pits the financial interest of the institution against the financial interests of students (the institution loses money if too many students opt out) and also the academic freedom of faculty (the institution loses money if too few faculty assign Pearson materials). It also means that the institution cannot be sure of the ultimate price they will pay at the time they sign the contract. This type of deal is emblematic of the concerns that are raised in this document.